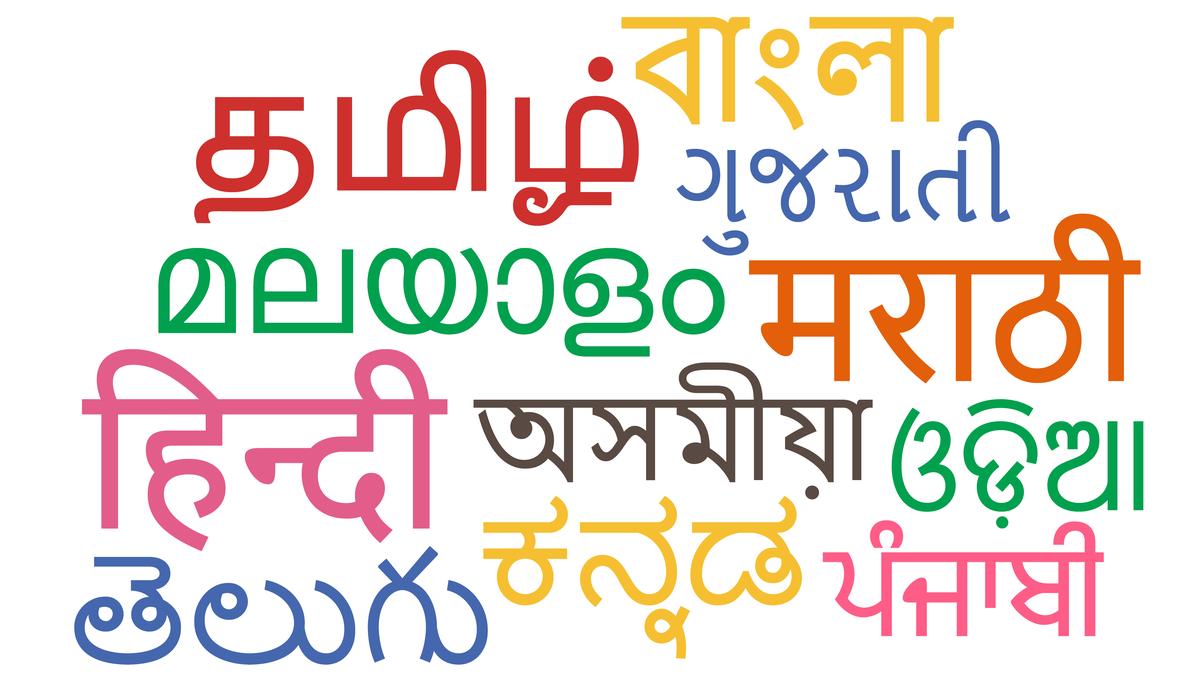

Globally, classical languages have been considered as those which have an ancient and independent literary tradition with a body of written literature considered to be classical.

| Photo Credit: Getty Images/iStockphoto

The story so far: The Union Cabinet approved classical status for five more languages earlier this month — Marathi, Bengali, Assamese, Pali, and Prakrit — by tweaking the criteria for the declaration. The announcement, which came days before the schedule for the Maharashtra Assembly election was announced, has led to a political war of words, with the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and the Congress claiming some credit for the fulfilment of the State’s long-pending demand. Beyond politics, however, scholars and academics hope that the new status will protect and enhance historic research, literary translations, and the modern fate of these languages.

What makes a language classical?

Globally, classical languages have been considered as those which have an ancient and independent literary tradition with a body of written literature considered to be classical. They are often not in use as spoken languages — such as Latin or Sanskrit — or are distinct from their modern versions.

When the new UPA-led Union government introduced the classical status for Indian languages in 2004, it defined them using three criteria: that its earliest texts or recorded history dated back over a thousand years; that it had a body of ancient literature considered a valuable heritage by generations of speakers; and that its literary tradition must be original and not borrowed from another speech community. Tamil was the first language declared to be classical.

In 2005, these criteria were tweaked to push back the historical requirement to 1,500 to 2,000 years and to stipulate that “the classical language and literature being distinct from modern, there may also be a discontinuity between the classical language and its later forms or its offshoots”. Under these norms, five more languages were declared as classical over the next decade: Sanskrit, Telugu, Kannada, Malayalam, and finally, Odia, which attained that status just a couple of months before the 2014 general election. No new classical languages were declared under two terms of the BJP-led NDA government.

How did the new classical languages attain this status?

Maharashtra put forth a proposal for Marathi to be declared as a classical language in 2013, but it was not approved under the criteria at that time. “The process actually started in 2012, when the Pathare committee was set up to develop the proposal with evidence from old documents. It initially submitted its report in Marathi, which then had to be translated to English. It was finally submitted to the [Union Culture Ministry’s] Linguistic Experts Committee in November 2013,” says Sadanand More, a Marathi writer and historian, and chairman of the Maharashtra State Literature and Culture Board. At that time, both Centre and State were ruled by Congress-led governments. In July 2014, then-Congress Chief Minister Prithviraj Chavan also presented the proposal to the newly elected Modi-led government at the Centre.

Over the next decade, the State government, led by BJP and then Shiv Sena factions, pursued the matter with the Centre. “It was not just the government, but a popular movement. Over a lakh people sent postcards to the President; MPs asked questions in Parliament, someone went to court…” says Dr. More. He said that Marathi has a rich literary tradition and at least 2,000 years of consistent history, claiming that Maharashtri Prakrit was an original language, unlike other forms of Prakrit which are derivative.

Ultimately, the Union government granted the request after 11 long years, on the eve of critical Assembly elections in the State, after the LEC again amended the criteria to allow for a wider definition of classical languages. In July 2024, the LEC removed the requirement that any proposed language’s “literary tradition must be original and not borrowed from another speech community”, and added the requirement that a classical language must include “knowledge texts, especially prose texts in addition to poetry, epigraphical and inscriptional evidence”. It also said a classical language “could be” distinct from its current form.

These new criteria paved the way for not just Marathi, but also Bengali and Assamese, which are also modern languages in current use. “We submitted a 392-page report to the Culture Ministry in March 2021 tracing the history of Assamese to prove its antiquity. Stone inscriptions go as far back as the third century AD. There are copper plates and manuscripts written on the bark of the Sanchi tree, as well as extensive folklore and folksongs in Assamese,” says Kuladhar Saikia, former president of the Assam Sahitya Sabha, who says the popular drive to protect Assamese comes from a colonial history of attempted language erasure. West Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee had, in January 2024, sent a four-volume report to the Centre, seeking classical status for Bengali on the grounds of concrete evidence proving that it existed as a written language as far back as the 3rd or 4th century BCE.

The new criteria also allowed for the inclusion of Pali and Prakrit, ancient vernacular languages used by the masses in their time in comparison to the Sanskrit used for Vedic ritual, which were adopted by Jainism and Theravada Buddhism.

What lies ahead for the newly declared classical languages?

“It is important that the language in which Nobel Prize winner Rabindranath Tagore wrote is recognised as a classical language, at a time when many people are reluctant to speak in Bangla,” says Nrisingha Prasad Bhaduri, a writer, historian and Indologist. “So many Bengali works are awaiting translation. Bengali dialects also need support. This will also help research proposals in Bangla to get central funds.”

“It is an acknowledgement that Marathi is important to the national culture, but it is more than just regional pride,” says Dr. More. “There is a provision for grants for language development and research, translation, Marathi teaching outside Maharashtra, and preservation of the older forms of the language and old texts.”

The Centre has funded universities for Sanskrit and Tamil and centres of excellence and university chairs for the other existing classical languages, as well as national and international awards. Central budget grants for classical languages have ranged from over ₹51 crore for Tamil over the last decade to ₹3.7 crore for Malayalam since 2020.

“There are so many rock inscriptions in Assamese which are yet to be deciphered, and this will support researchers seeking to study the ancient language and translate Assamese classics,” says Mr. Saikia. “But we also hope it will give a fillip to the learning and use of modern Assamese, given the rise of English-medium schools. Our report proved that our language has deep roots. Now we must ensure that it also has support to spread its leaves and branches.”

Published – October 20, 2024 02:20 am IST