The last time I met Dr Manmohan Singh at his residence some days ago, he was frail but as always, his gracious self, thanking me for keeping him briefed on what was happening around the world. He was a good listener, raising sharp questions and offering well-considered comments. Since the end of his 10-year tenure as PM in 2014, I used to call on him at regular intervals and engaged him in lively conversations on the latest developments across the world. Even as he grew weak and beset with ailments, his mind was alert and nimble. It was as if my role as foreign secretary, and later as his special envoy in the PMO, had continued without interruption. He would always offer his own perspectives and share unexpected reminiscences about his encounters with the various movers and shakers in the world. He had a mischievous sense of humour accompanied by a gentle twinkle of the eyes. I will miss these memorable moments.

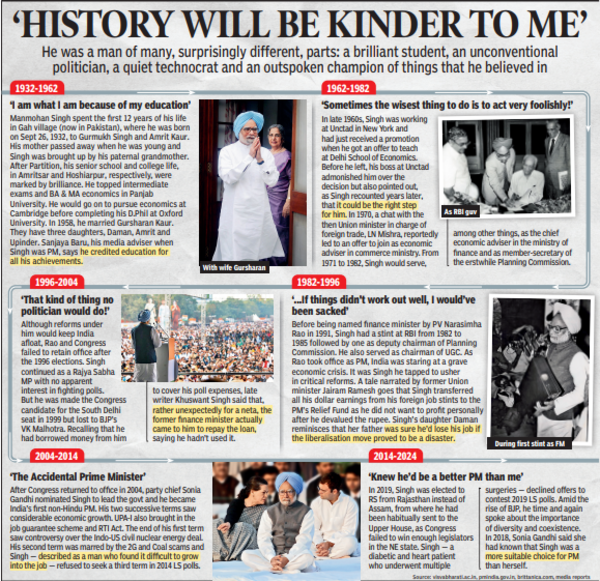

Dr Singh was an under-rated PM, whose gentle manners and old-world courtesy obscured a keen intellect, strategic wisdom and a willingness to take risks if a matter of vital national interest was involved. This was evident when he pioneered the path-breaking economic reforms in 1990 as finance minister under PM Narasimha Rao. I was joint secretary in the PMO then, looking after external affairs and had a ring-side view of the pulls and pressures he was subjected to in pushing through the new economic policies. Much later in one of our conversations, he said that those days he carried a letter of resignation in his pocket since he never knew if and when a reversal may come. The same willingness to take a risk and be willing to sacrifice office was evident in the tenacity with which he pursued the India-US nuclear deal between 2005-08 even when his own party was ready to call it quits.

As PM, Dr Singh deliberately sought opinions from a wide range of sources. He would emphasise the need to build a consensus around policies but would pick and choose what was important enough to take a stand on and where it would be best to let sleeping dogs lie. In retrospect, I think the choices he made were sound and judicious even though I may have found it frustrating at times. After the Mumbai attack in 2008, there was pressure on him to approve swift retaliation against Pakistan. He did consider it, but after meeting with chiefs of Armed forces, he decided against it and I think in retrospect rightly so.

There would be occasions when he wouldn’t follow my advice and I would be expected to deliver on whatever policy had been adopted. But never once did I feel that I would in any way suffer if I expressed a viewpoint that I knew he disagreed with. Once on a climate change-related issue I was inclined to take a strong position while he felt that India should be seen as “part of the solution rather than as part of the problem.” I was somewhat obstinate in holding the view that it was the advanced countries that refused to be part of the solution and not India. Later, I felt that I had perhaps been out of line in expressing my disagreement. The next day, I apologised for my behaviour and said it was wrong of me to insist on a contrary position. Dr Singh smiled and reassured me, saying that if I started playing his own words back to him, there would not be much value in having me as an adviser. He was self-assured enough to handle opinions divergent to his own with grace and equanimity.

During my eight years of serving under him, I was witness to the respect with which he was held by his foreign counterparts. His assessment of global economy was always sought at bilateral and multilateral summits. I can say from personal experience that President George Bush had developed a relationship of trust and affection with Dr Singh. At critical moments in the negotiation of Indo-US nuclear deal, it was Dr Singh’s personal intervention with President Bush that helped clear the logjam. India gained international stature during his term as PM and his own reputation as a statesman and a wise-thinker was part of it.

He said that history would judge him kindly. I think India was fortunate to have his gentle but firm hand at the wheel when it needed it most. Power exercised with empathy and a touch of grace achieves much more than a display of muscularity does. He did India proud.

(Author is ex-foreign secretary and ex-special envoy of PM Manmohan Singh for Nuclear Affairs and Climate Change)