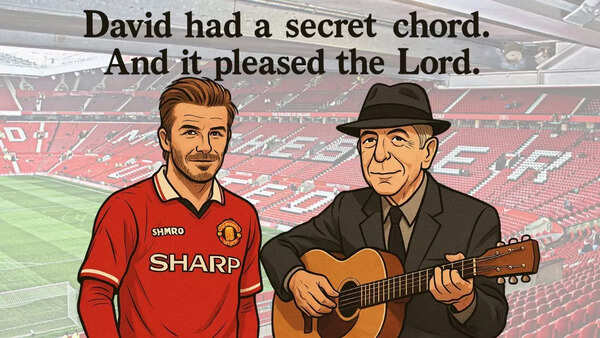

“Beckham, into Sheringham… and Solskjaer has won it!”“Manchester United have reached the promised land.”The corner came in like a hymn. Beckham’s delivery—whipped, precise, inevitable—was scripture in motion. In the annals of football, there are players who pass, players who dribble, players who score. But there was no one who could bend it like Beckham. Or to paraphrase Leonard Cohen: David had a secret chord that pleased the Lord.For United fans of the current vintage, it’s hard to forget how good Beckham and his mates were and how terrifying it was for opposing teams when they played together. Because at that moment we were all in a Gurinder Chadha film, hoping to bend it like Beckham and if we couldn’t copy his mohawk hairstyle, much to the chagrin of mothers and teachers.You had Ryan Giggs running like a cocker spaniel chasing a silver piece of paper. You had Roy Keane looking at you menacingly as he covered every blade of grass. You had Paul Scholes hitting the ball with such power that it took Sir Alex Ferguson’s breath away. And you had David Beckham pinging crosses and passes with such accuracy that it seemed barely human.It’s easy to forget now, with the beard oils and whisky launches, the sarongs and showmanship, that before he became a brand, Beckham was a baller. And not just a decent one. A magnificent one.He wasn’t a dribbler like Messi. He didn’t roar like Rooney. He didn’t shrug off defenders like Ronaldo. He didn’t drop his shoulder like Cruyff. But when Beckham struck a ball, it obeyed. As if Newtonian physics had made an exception for a young working-class lad from London. And then the universe followed for its rules of celebrity.Born May 2, 1975, he’s now 50. Half a century. And yet, there are days he still looks like that boy from Leytonstone, walking up to a dead ball with a gaze so focused you’d think the world was about to tilt. And often, it did.

The Lad from Leytonstone

The new Knight of the Realm wasn’t born into privilege, but he was born with an obsession. His father was a kitchen fitter and a rabid Manchester United supporter. His mother was a hairdresser. Together, they gifted him football boots, not fairy tales. The middle name “Robert” was a nod to Bobby Charlton. Not that he needed the hint.While other kids played for fun, Beckham played to become. Teachers would ask what he wanted to be. He’d say, “A footballer.” They’d laugh. But there’s no dissuading a kid who knows his dharma.At age 14, he joined United as a youth trainee and was soon part of the club’s golden nursery—the Class of ’92. In fact, Ferguson, contrary to his image as the Devil reincarnate, would let Beckham hang out with the first team and clean their boots, a task the young Beckham thought was the greatest chore in the world.In 1995, with United letting go of seasoned names like Mark Hughes and Paul Ince, the kids were thrown into the fire. They lost 3-1 to Aston Villa. Cue Alan Hansen’s infamous line: “You can’t win anything with kids.” Except these weren’t regular kids.By the end of that season, Beckham and the boys had won the league. Of course, they had a wry Frenchman named Eric Cantona to help them along.But for Beckham, the true breakthrough moment came the season later when he lobbed the Wimbledon keeper Neil Sullivan from his own half. Even Eric Cantona was ostensibly impressed with the young man who worshipped him. And once Cantona retired prematurely to follow more philosophical pursuits like the proverbial seagulls, David Beckham begged for and inherited his shirt: the hallowed number 7.

The Treble. The Truth.

Yet it was the 1998-99 season that truly made him, to borrow a line from his father, grow into a man. The 1999 Champions League final was, for Beckham, a remarkable redemption arc that began with the horror show of France 1998 when he was sent off for a cheeky pub-side hack on Diego Simeone, who fell like he was auditioning for the slasher horror movie Hostel where someone had cut his Achilles tendon.David Beckham became the most hated name in England, to the point that his effigies were burned all around. But that actually forged the siege mentality that allowed Ferguson to mould his team into world beaters.And Beckham was instrumental in that season, scoring 9 goals and providing 20 assists, though numbers hardly tell the full tale of Beckham’s contributions. He scored the first goal in the FA Cup semi-final replay against Arsenal, he got the first goal in the final game of the league season against Tottenham, and delivered the precise corners that helped United triumph in the very last minute against Bayern Munich.The great lie of football is that it’s a game of moments. It isn’t. It’s a game of margins. Beckham operated in the margins with the precision of a surgeon and the romance of a poet. It would appear that he had the secret chord that pleased the Lord. His right foot was less a limb and more a compass, pointing north every time the team lost its way.

The Right Boot of God

If Maradona had the Hand of God, Beckham had the Right Boot of God.It wasn’t just that he could cross. It was that he could cross on command, under pressure, from impossible angles. His delivery was so accurate, it felt like watching a heat-seeking missile disguised as a football. He made the football curl, dip, hover, and hum through the air—like it had fallen in love with where it was going.He still holds the record for most free-kick goals in Premier League history: 18. More than Cristiano Ronaldo. More than Henry. More than Kevin de Bruyne. More than anyone else in the history of the English game.And it wasn’t just the number—it was the weight of the moments. The 93rd-minute free-kick against Greece to send England to the World Cup. The whipped-in goal against Leicester from wide. The relentless deliveries that made strikers look better than they were. Give Beckham one moment, and he gave you a masterpiece.He didn’t just hit the ball. He whispered to it. And it listened.

Arise, Sir Goldenballs

David Beckham was never the best player in the world. But he might have been the most important. He changed the image of a footballer. He built a brand before Instagram. He bent free-kicks, and then bent the arc of what an athlete could be.Goldenballs. Spice Husband. Captain. Galáctico. Icon. Knight.Yes, he’s finally a knight now—despite what the c***s on the honours committee thought for years. And through it all—through the fame, the fragrance ads, the fashion shoots and front pages—he never lost that one thing: the secret chord. The one that pleased the Lord. And the Stretford End.