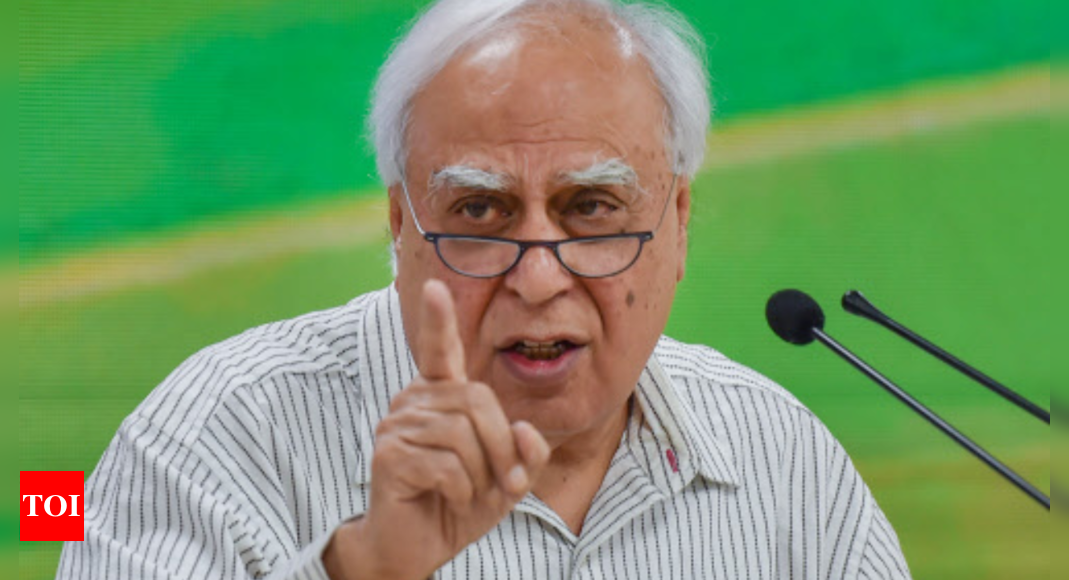

NEW DELHI: Their duel constituted one of the highlights of the hearings in the case over the challenge to revocation of J&K’s special status. On Wednesday, SG Tushar Mehta and senior advocate Kapil Sibal faced off again, bringing to the court the same intensity that has become the hallmark of their encounters.

Sibal, HRD minister in the UPA government, was first off the blocks, opposing the government backing Allahabad HC’s 2006 decision quashing certain provisions of the Aligarh Muslim University Act.He said the Centre was duty bound to support a law enacted by Parliament and termed the Modi government’s stand “disconcerting”.

Sibal was arguing for validating the 1981 amendments to the AMU Act through which it was redefined that AMU, the new avatar of Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental (MAO) College, was a university established by the Muslims of India. Earlier, the same provision read ‘university means the Aligarh Muslim University’.

A clause was also introduced in Section 5 of the Act in 1981 to allow the university to promote educational and cultural advancement of Muslims in India. The HC had struck these down as unconstitutional as it went against the SC’s 1967 judgment in Azeez Basha case declaring AMU to be a non-minority institution. The high court had also quashed 50% reservation for Muslims in PG courses.

Sibal said, “Even if I assume that the 1981 Act is bad, it still is a parliamentary statute. Fine, at present it is void. But can a government ever make a submission to the court contrary to a parliamentary statute, even if it is void? The executive cannot go against a parliamentary statute even if the court has struck it down.

“Every day, statutes are struck down by HCs. This is the first time the government has said it is opposed to the 1981 Act after supporting it in HC. They say they can change their mind. Yes, they can but only when it relates to an executive decision and not when the statute was passed by Parliament. It is a serious issue.”

The line of reasoning gave an opening to SG Mehta to point out that Sibal’s stand would also require the government to support laws, including the infamous, Emergency-era 39th constitutional amendment by which the Indira Gandhi government had suspended fundamental rights. “Before a constitution bench of the SC, it is the duty of the government to assist by placing the law in the correct possible manner. The 1981 Act has been rightly struck down by HC. I (the government) can always support the HC decision,” Mehta said as he countered the argument about the government getting locked into the stand it may have taken.

Discounting the SG’s rebuttal, the essence of Sibal’s reservations over the government’s U-turn on the 1981 Act was that a government must continue to support a Parliament-enacted statute even after it is struck down by a constitutional court.

Sibal, HRD minister in the UPA government, was first off the blocks, opposing the government backing Allahabad HC’s 2006 decision quashing certain provisions of the Aligarh Muslim University Act.He said the Centre was duty bound to support a law enacted by Parliament and termed the Modi government’s stand “disconcerting”.

Sibal was arguing for validating the 1981 amendments to the AMU Act through which it was redefined that AMU, the new avatar of Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental (MAO) College, was a university established by the Muslims of India. Earlier, the same provision read ‘university means the Aligarh Muslim University’.

A clause was also introduced in Section 5 of the Act in 1981 to allow the university to promote educational and cultural advancement of Muslims in India. The HC had struck these down as unconstitutional as it went against the SC’s 1967 judgment in Azeez Basha case declaring AMU to be a non-minority institution. The high court had also quashed 50% reservation for Muslims in PG courses.

Sibal said, “Even if I assume that the 1981 Act is bad, it still is a parliamentary statute. Fine, at present it is void. But can a government ever make a submission to the court contrary to a parliamentary statute, even if it is void? The executive cannot go against a parliamentary statute even if the court has struck it down.

“Every day, statutes are struck down by HCs. This is the first time the government has said it is opposed to the 1981 Act after supporting it in HC. They say they can change their mind. Yes, they can but only when it relates to an executive decision and not when the statute was passed by Parliament. It is a serious issue.”

The line of reasoning gave an opening to SG Mehta to point out that Sibal’s stand would also require the government to support laws, including the infamous, Emergency-era 39th constitutional amendment by which the Indira Gandhi government had suspended fundamental rights. “Before a constitution bench of the SC, it is the duty of the government to assist by placing the law in the correct possible manner. The 1981 Act has been rightly struck down by HC. I (the government) can always support the HC decision,” Mehta said as he countered the argument about the government getting locked into the stand it may have taken.

Discounting the SG’s rebuttal, the essence of Sibal’s reservations over the government’s U-turn on the 1981 Act was that a government must continue to support a Parliament-enacted statute even after it is struck down by a constitutional court.